Jeffrey Wright handles the truth in "American Fiction"

Cord Jefferson's directorial debut is extraordinary

The opening scene of “American Fiction” cuts right to the chase. Thelonious “Monk” Ellison (Jeffrey Wright) is teaching a class about a well-known short story by Flannery O’Connor. While the title of the story is clearly visible to the audience as the scene unfolds, I’ll refer to it here as The Artificial N-word, but you know better.

One of Monk’s students objects to seeing the N-word, let alone reading the story. As the two of them spar over a super fraught six-letter insult, they exasperate each other; one storms out after the other makes a sarcastic comment.

Monk’s colleagues immediately suggest he “take a break” and visit family in Boston. Thus, he reconnects with his mother (Leslie Uggams), his sister Lisa (Tracee Ellis Ross), and his brother Cliff (Sterling Brown), as well as the housekeeper Lorraine (Myra Lucretia Taylor). Soon he’s dating his neighbor Coraline (Erika Alexander) and volunteering as a judge for a book festival. Enter Sintara Golden (Issa Rae), best selling Black writer herself.

As hard as it is, Jeffrey Wright handles the truth in “American Fiction,” a very relatable family drama that also roasts the publishing world. While the book industry is in thrall to Sintara Golden’s use of African American Vernacular English (AAVE), Monk objects to her pandering to White readers.

He is so mortified by this, he types out a satirical response using a very specific pseudonym, Stagg R. Leigh. Unintended consequences soon follow as Monk/Stagg’s literary agent sells the parody to the highest bidder. And what he originally called “My Pathology” now becomes “My Pafology.” Long live Ebonics!

Meanwhile, Monk’s family drama continues. His mother clearly suffers from a broken heart with good reason. Her cognitive decline accelerates as Cliff deals with the end of his marriage and the disappearance of gay bars. Finally, Lorraine finds love, and so do Coraline and Monk.

But it’s his book that finds the most love. Still, Monk is more horrified by his unplanned publishing success than Sintara’s approach to monetization. In a last ditch effort to derail things, he convinces the publisher to re-brand his book as “Fuck.”

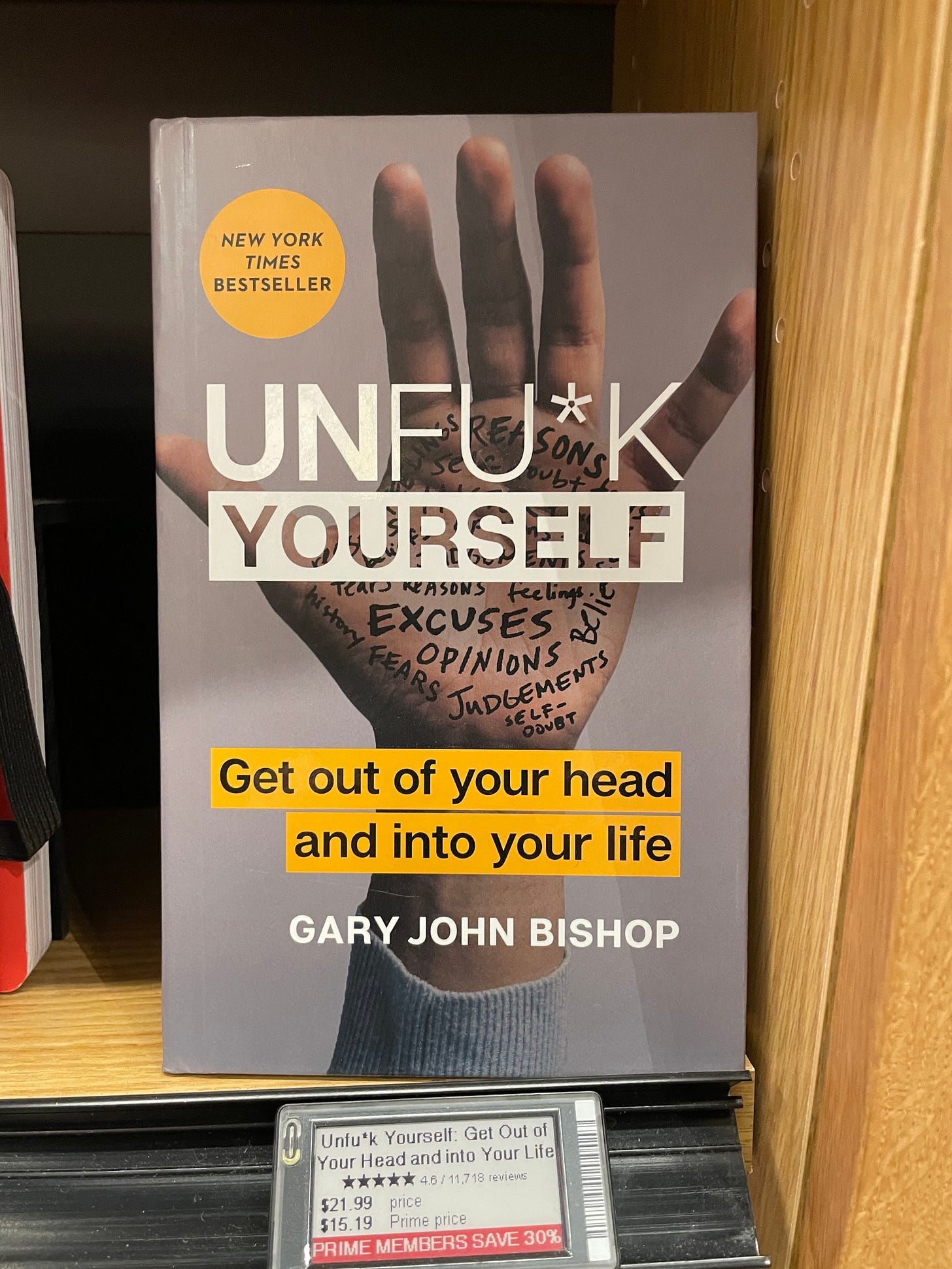

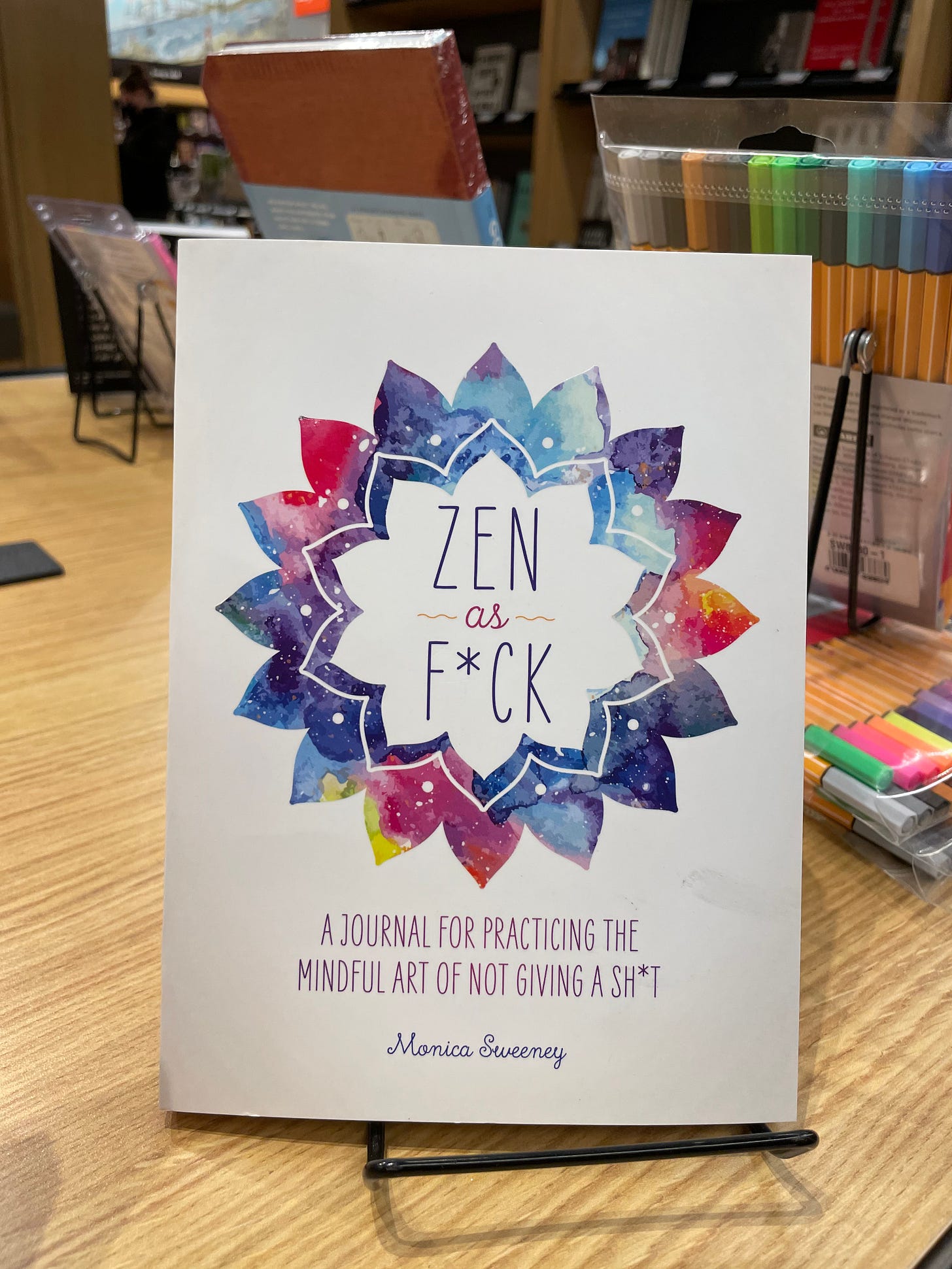

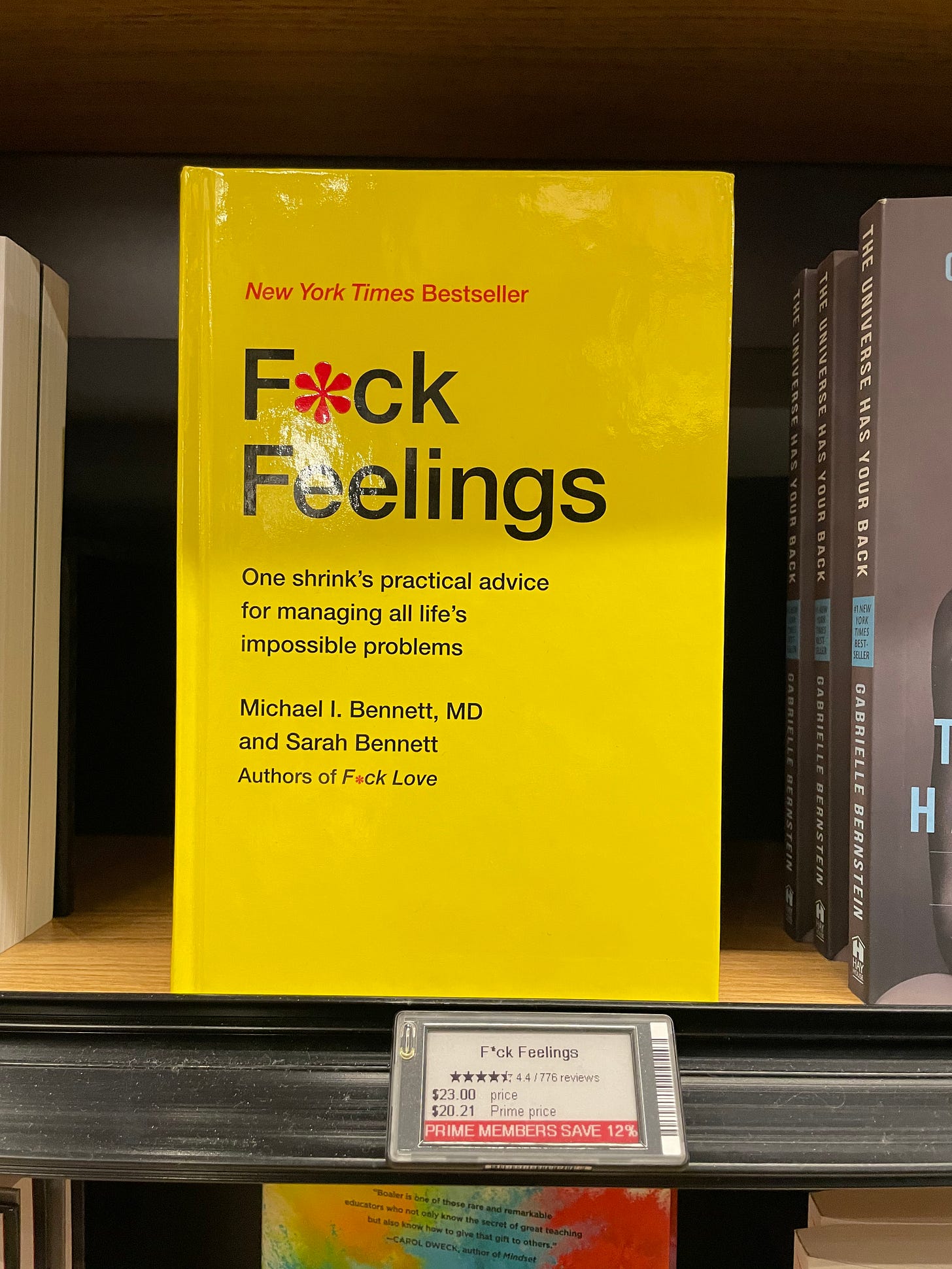

Later on he realizes, “The dumber I behave, the richer I get.” Plus, he might be a marketing genius, judging by these covers:

Gazing at bookstore displays also brings me to my favorite scene. When Monk searches for copies of his earlier tomes at the local bookstore, he finds them tucked away in the African-American studies section. Agitated, he asks a clerk why they’re not on the general fiction table. Hearing no credible reply, Monk relocates them all to a more visible spot.

The night before I saw “American Fiction,” I watched Julia Louis-Dreyfus in last year’s “You Hurt My Feelings.” Another writerly flick that wrestles with honesty in both comedic and dramatic ways, it focuses on family as well. And perhaps not coincidentally, Louis-Dreyfus’s character repositions her memoir at a bookstore, too. Honestly, these two movies would make for a nifty double feature.

The filmmaking team behind “American Fiction” also offers several possible endings for the audience’s consideration. This is reminiscent of 2022’s “The Quiet Girl,” which left viewers with hope for the best in the final frame. In this case though, the device works to make us think critically before acting foolishly.

In summary, Jeffery Wright handles the truth phenomenally well in “American Fiction.” Cord Jefferson’s directorial debut is equally remarkable, given his double duty screenwriting role. He truly serves up a smoldering, satisfying embrace of Percival Everett’s 2001 novel “Erasure,” on which the film is based.

Just as interesting? Everett’s book called “I Am Not Sidney Poitier.” How I’d love to see the screen adaptation of this!

For now, guess who’s coming soon to a theater near you?